Locked Up in Liberty: When Surveys Reveal Hard Truths

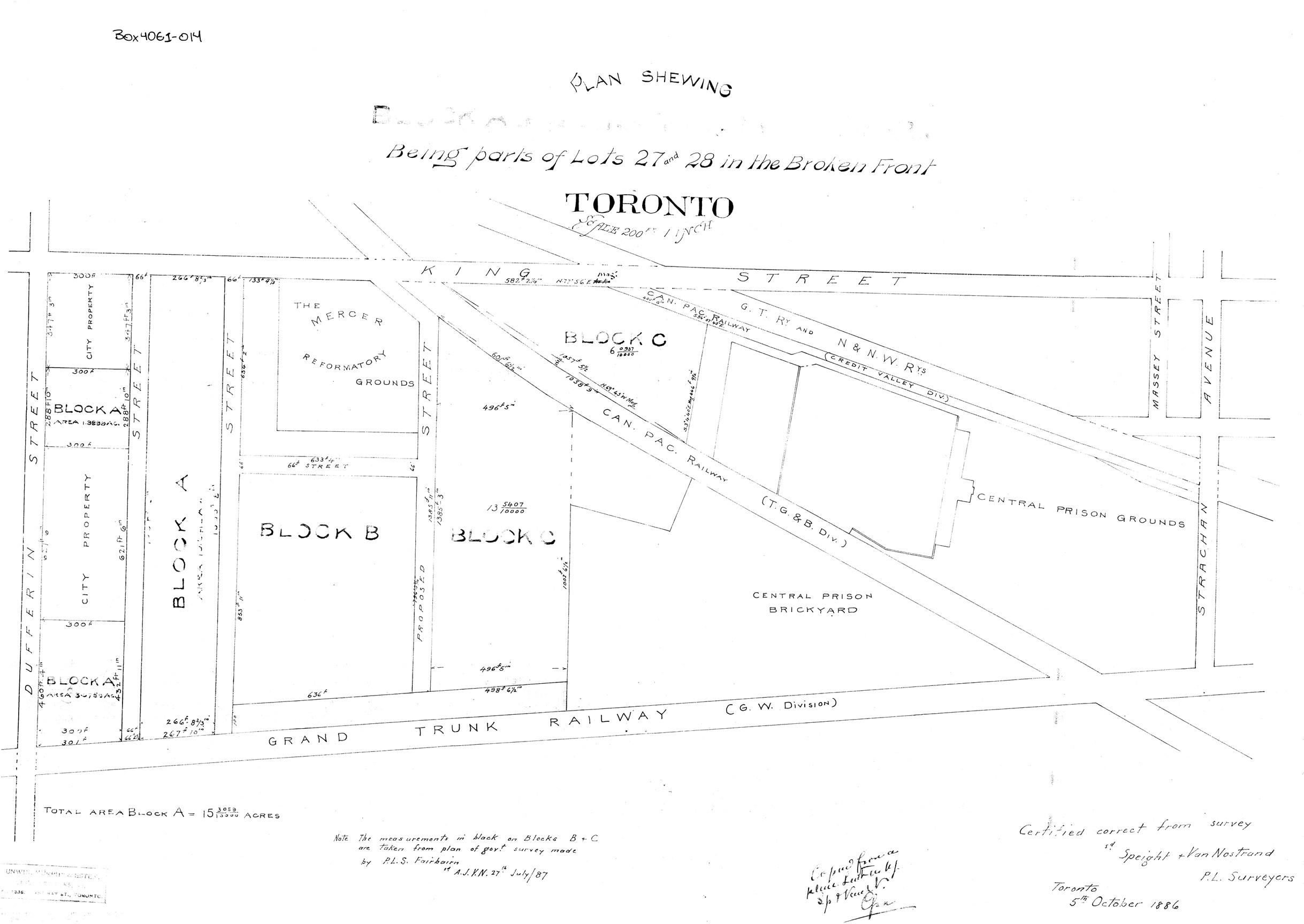

Liberty Village is one of Toronto's youngest neighbourhoods. Many assume this area was nothing more than an industrial zone before it became overrun with tech start-ups and yoga studios. Wondering about the history, I pulled up some old surveys of the area, hoping to locate one that told the story behind this trendy neighbourhood. It did not take me long to find a plan dated 1886, which showed two large buildings. One labelled, ‘The Mercer Reformatory’ and the other, ‘Central Prison Grounds’. The word “ironic” immediately comes to mind. “Liberty Village”, a name suggesting freedom, was the foundation for the very grounds where people were anything but liberated.

The Mercer Reformatory

The Andrew Mercer Reformatory for women opened in 1880 on what is now King Street West in Liberty Village. It was Canada's first women-only prison, operating until 1969. To the public, it was promoted as a place of reform, where Victorian norms, such as obedience and domestic skills, could be instilled in its female inmates. Unfortunately, this structure was more of a facade, and the prison gained a notorious reputation for harsh discipline, riots, abuse, and controversial treatment practices.

In addition to the horrid conditions within the building, the reason why women ended up incarcerated was equally concerning. In many circumstances, women were not being held for violent or illegal crimes, but rather morally defined offences. Women who were deemed “incorrigible” or defiant by their parents, including those living with a man, pregnant outside of wedlock, struggling with poverty or mental health, or using alcohol, could be committed to the Mercer Reformatory, often at the request of their own family members. Women who refused to conform to social “norms” were seen as a problem that could be locked away. A grand jury investigation into the abuse and mistreatment of its inmates finally forced the closure of the Mercer Reformatory in 1969; it was demolished later that same year. Today, this is the grounds for the Allen A. Lamport Stadium.

Toronto Central Prison

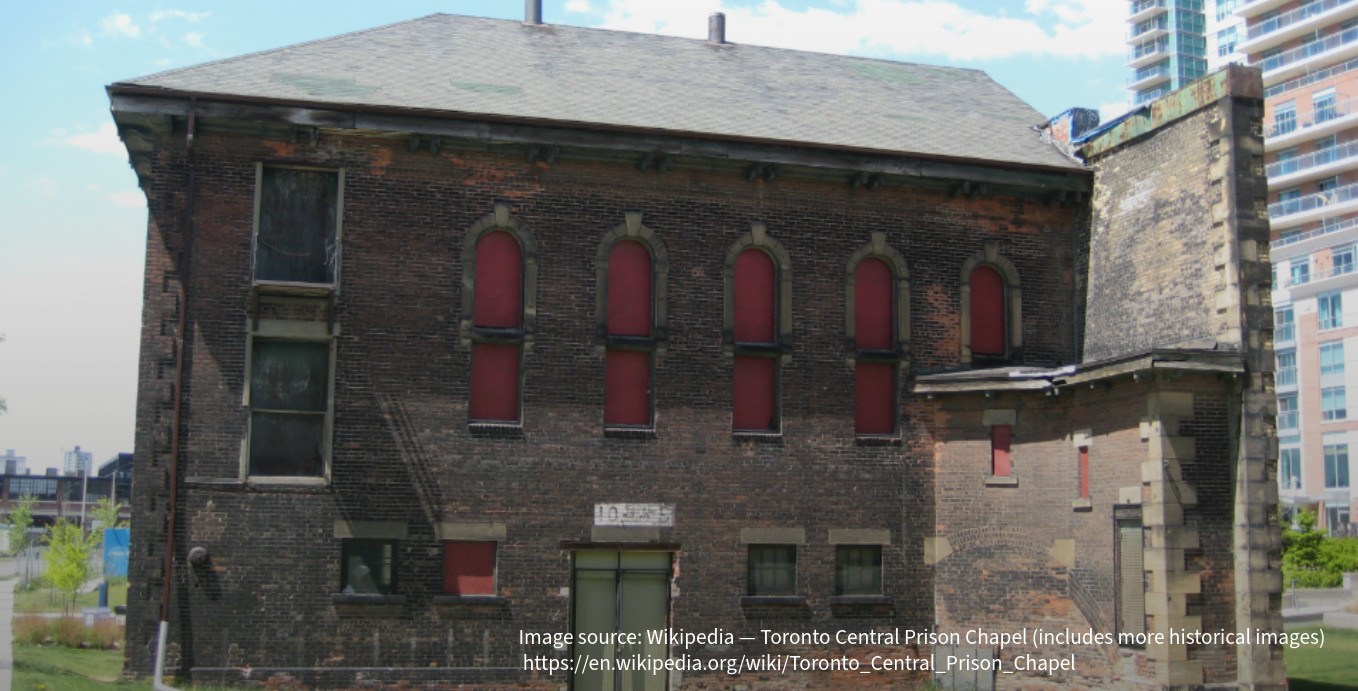

East of the Mercer Reformatory was the Toronto Central Prison. It had opened in 1873 as a maximum-security facility. In contrast to the women's prison, inmates at the Central Prison were often repeat offenders or men serving longer sentences, though punishment styles were equally gruesome. The men's prison was designed for punishment, discipline and labour. Rotten food, corporal punishment and death are said to be a part of life within the walls.

Just south of the main Prison was the Central Prison Brickyard, as illustrated in the 1886 survey. Inmates worked and built many of their own buildings on the grounds, including the prison chapel, which still stands today in Liberty Village Park.

The Toronto Central Prison closed in 1915 when criticisms of the cruel living conditions, overcrowding and outdated approach to incarceration became widespread. While this closure occurred more than 50 years before the Mercer Reformatory shut its doors, the survey record shows how both institutions shaped land use in Liberty Village long before the neighbourhood’s modern transformation.

Historic survey source: Protect Your Boundaries database (original survey plans owned by Krcmar Surveyors Ltd.).

Where Freedom Walks Began

The name ‘Liberty Village’ may seem at odds with the area's history of horrible occurrences for the better part of a century, but it does have a meaningful connection to the past. The name Liberty Village came from the well-known Liberty Street. This was the first street that former inmates would walk down upon their release from the Mercer Reformatory and the Central Prison. It could also be symbolic of a deeper meaning: freedom for those who once lived there as inmates, and the land metaphorically washed of past mistakes.

Lines on the Map and Beliefs in Practice

The transformation that this area has undergone, from institutional imprisonment grounds to a trendy urban neighbourhood, not only highlights the dramatic changes in land use in Toronto, but also how far we have come as a society.

Land use is directly impacted by cultural evolution and societal needs. As the city grew outwards, the grim prison no longer fit the urban fabric of the land, nor did it reflect the attitudes of Toronto’s correction system.

Historic surveys have a wonderful way of bringing the past to life. They show us how land was used and bring attention to the beliefs and attitudes of the past that would no longer fit in modern society. With the help of surveys, we get a powerful reminder that environments are often a direct reflection of the social systems that created them.

References:

- Andrew Mercer Reformatory Project – information about the Mercer Reformatory, research, and heritage plaque details.

https://andrewmercerreformatory.org/ - Heritage Toronto — Bad Girls Map: Mercer Reformatory History – local history and interpretation of the Mercer Reformatory and related institutions.

https://www.heritagetoronto.org/explore/bad-girls-map/mercers-reformatory-history/ - Central Prison | Toronto Historical Association – historical description of the Central Prison (location, operation, layout, labour use).

https://www.torontohistory.net/central-prison/ - Heritage Toronto — Central Prison Historic Overview – additional context on the Central Prison (dates in operation, location, scale).

https://www.heritagetoronto.org/explore/bad-girls-map/central-prison-history/ - Liberty Village BIA — History of Liberty Village – neighbourhood history including Central Prison and naming context for Liberty Street.

https://www.libertyvillagebia.com/love-liberty/history-of-liberty-village